European businesses, investors, and talent are all vying for a ticket on the metaverse hype train. Even political heavyweights are making moves — or, at least, pronouncements.

French President Emmanuel Macron wants to build “a European metaverse” to challenge US and Chinese tech giants. The EU’s digital chief, Margrethe Vestager, meanwhile, is mulling new antitrust regulation. But their ambitions are a long way from being realized.

“The reality is there is no European big tech player of relevance in that whole metaverse future,” says Rolf Illenberger, the cofounder of Munich’s VRdirect, a virtual reality platform for enterprises. “It’s being defined by US and Asian players. Those are the two regions where this technology is going to develop.”

In the US, the tech titans of Meta, Microsoft, and Apple are set for leading roles, while Roblox and Decentraland already offer popular proto-metaverse platforms.

Their biggest global challengers are based in Asia. Bytedance, the owner of TikTok and VR hardware giant Pico, is the strongest contender, but further competition is emerging at the likes of Huawei, Tencent, and the Sandbox virtual world.

European startups lag behind their US and Asian counterparts.

Europe, by contrast, is largely limited to niche operators and startups. These range from Finland’s Varjo, which produces upmarket headsets, to Estonia’s Ready Player Me, a cross-game avatar platform that recently bagged $56 million in a funding round led by VC giant Andreessen Horowitz.

Jake Stott, CEO of Web3 and metaverse ad agency Hype, is optimistic that Europe’s renowned fintech sector can produce future payment providers in the space. He acknowledges, however, that they face significant challenges.

“Historically, European startups have lagged behind their US and Asian counterparts when it comes to producing unicorns,” he says. “Europe also trails behind the US in terms of venture capital raised. This is perhaps one of the areas where government support can help the continent’s fledgling metaverse ecosystem — by removing barriers to growth and creating incentives for VCs.”

Europe’s metaverse funding problem

Petri Rajahalme has his own plans to plug the funding gap. The Finnish entrepreneur and his business partner, Dave Hayes, recently launched FOV Ventures, the first VC firm to specialize in early-stage metaverse companies in Europe. In March, the duo announced a €25m fund for startups at the pre-seed or seed stage.

“We’re not lacking in talent, that’s for sure,” says Rajalhlme. “If you look at historical M&A, a lot of the companies that US [businesses] have snagged up are talent coming from Europe… The big question is how do you keep that talent in Europe?”

The talent pipeline flows towards the best financial incentives. Finland, for example, provides free and high-quality education, but the salaries offered upon graduation don’t compare to those in Silicon Valley.

EU grants can provide some support with scaling, but applying for them is immensely time-consuming and the financing is limited. FOV Ventures prefers to keep talent in Europe by providing early-stage funding and go-to-market expertise.

A key component of the strategy is an “edge network” of metaverse professionals from established players, such as Meta and Decentraland. These experts can provide funding and advice on working with big platforms.

Rajahalme also wants Europe’s investors to work together to challenge US resources.

“As VCs, we should be very collaborative here within Europe to share knowledge, deal flows, and insights — and also help at the grassroots level,” he says. “This is a big wave, but it’s a wave that’s just starting up and we have to get more and more people involved.”

Rajahalme has invested in this wave since 2016, but he admits that the metaverse only crept into the mainstream after Facebook rebranded as Meta.

That doesn’t mean the metaverse is now widely-understood. Indeed, the nebulous nature of the concept poses both problems and opportunities.

Building the unknown

Members of both the European Commission and Parliament have called for regulation of the metaverse. There is one problem, however: they don’t yet understand exactly what they’re regulating.

“As a legislator, we have now to think about how we can regulate something [that] is not there, or [that] is existing already but in a smaller dimension,” said MEP Axel Voss at a recent roundtable.

Definitions of the metaverse abound. Neal Stephenson, who coined the term in his 1992 novel Snow Crash, describes the real-life version as a “3D internet.” Mark Zuckerberg, meanwhile, envisions “a virtual environment where you can be present with people in digital spaces” and “an embodied internet that you’re inside of rather than just looking at.”

Rajahalme prefers the description given by fellow investor Matthew Ball:

“A massively scaled and interoperable network of real-time rendered 3D virtual worlds that can be experienced synchronously and persistently by an effectively unlimited number of users with an individual sense of presence, and with continuity of data, such as identity, history, entitlements, objects, communications, and payments.”

All these definitions have room for numerous use cases — and charlatans.

Virtually real or just assorted buzzwords?

If you trust Meta (and who wouldn’t?), the metaverse will let us move seamlessly between immersive digital spaces for work, education, leisure, and seemingly any other aspect of our physical world.

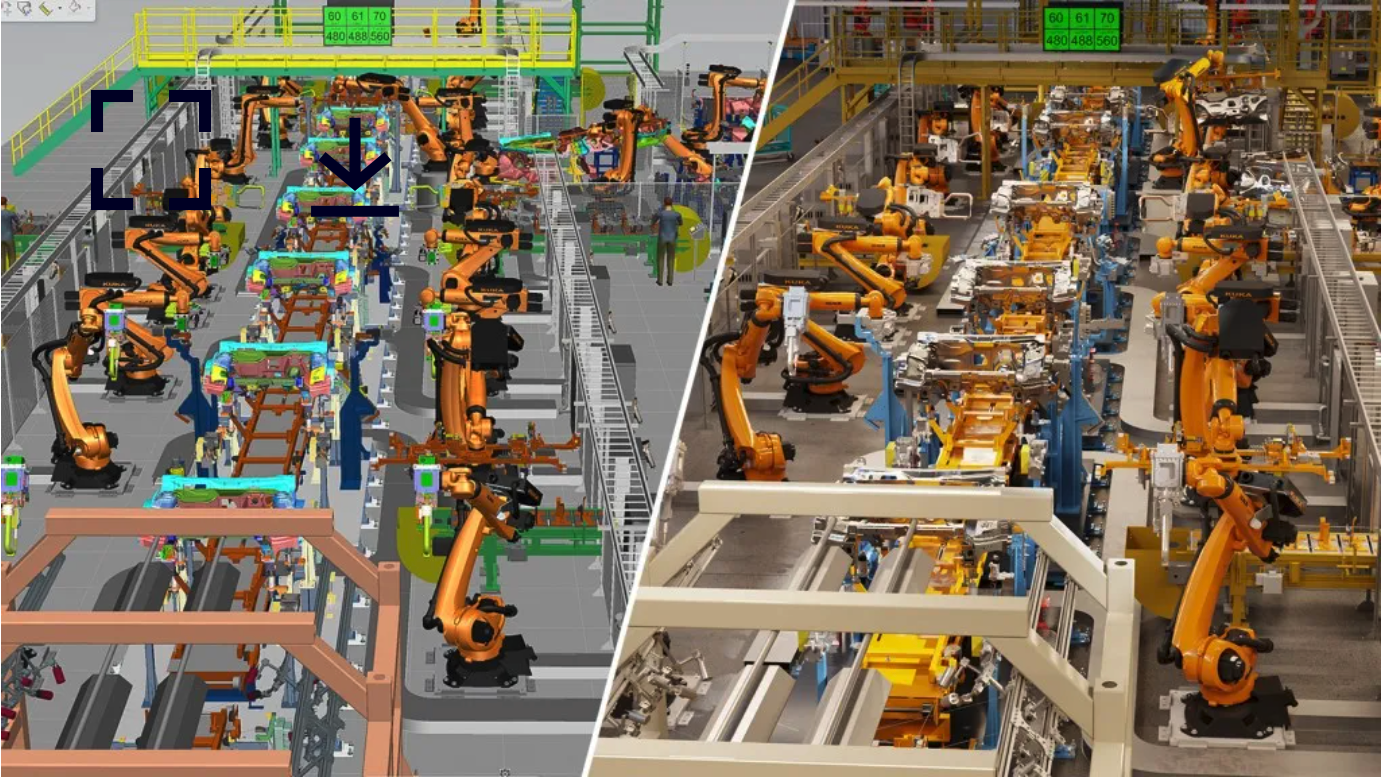

Some elements of this grand vision already exist. Virtual worlds are mainstays of online gaming, while VR vacations, immersive workplaces, AR training simulations, and “industrial metaverses” are also available to consumers.

This multitude of applications can play to the strengths of various European ecosystems. The Nordics, for instance, can harness its stellar gaming sector, while Germany’s industrial economy provides promising foundations for B2B services in the metaverse.

Critics, however, argue many “metaverse” vendors are merely repackaging existing technologies under an all-embracing buzzword. Their individual applications are also far from integrated. Any attempts to impose interoperability across platforms will be fraught with design challenges.

Illenberger, the VRdirect founder, has further doubts about the metaverse becoming decentralized. He predicts that Chinese and US big tech firms will remain gatekeepers to the dominant platforms.

“It’s going to be Meta, it’s going to be Apple, it’s going to be Bytedance — they’re going to control the ecosystem,” he says. “If you’re an app developer, you could develop an app for a Varjo, but your target audience will be [tiny]. So what you’re going to do is develop apps for Meta and Apple.”

These future metaverse rulers are now entering the crosshairs of EU lawmakers, who proclaim that strong data protection, and antitrust regulation are competitive advantages.

Not everyone agrees.

Setting rules

Some metaverse businesses, developers, and investors are concerned that EU regulation impedes innovation.

FOV Ventures founder Rajahalme shares an anecdote about a panel discussion on artificial intelligence developments in the US and China. The EU representatives in attendance said their ambition was to become the best regulators of AI.

“That’s like if when you started manufacturing cars, the Europeans said we want to be the best at making stop signs,” he jokes.

It’s a nightmare to comply with European data privacy rules.

Illenberger, whose company provides customized VR experiences for businesses, has witnessed the downsides of heavy-handed regulation.

One problem arose from VR headsets using outward-facing cameras to identify surroundings. They can therefore easily breach EU requirements for consent from anyone who could be accidentally filmed in a workplace.

These risks have led big organizations such as Siemens to introduce dedicated VR rooms that reduced the risk of violations. Yet these facilities are inconvenient for some businesses — and unaffordable for others.

“It’s a nightmare to even use metaverse technologies in compliance with European data privacy laws,” he says. “You have to film your environment in order for the device to work.”

The speeds at which such rules are changed can hamper innovation — and push trailblazers towards Asia or the US.

The reality of a European metaverse

While European companies can play important roles in the metaverse, Macron’s dream of competing with global tech giants is fanciful.

Instead of battling the incumbents, European firms may find more success by working with them. VRdirect, for instance, has built a business on supporting headsets designed by Meta, Pico, and HTC.

Illenberger argues such interoperability provides opportunities in the fragmented market. He’s also confident his company can benefit from stringent EU regulations, as businesses will seek his services over Silicon Valley stalwarts with scant interest in the rules.

“To some extent, this is a competitive advantage for us,” he says. “But in terms of Europe as a region versus the US and Asia, it’s a big roadblock.’

As for Macron’s vision of a European metaverse that competes with the tech titans while protecting the continent’s rules and culture?

“That’s wishful thinking.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.