In the fiercely contested smartphone market, photography can be a key battleground. Alongside the insatiable desires for better batteries, durability, storage, and processing, camera quality consistently ranks as a key factor when choosing a phone.

At CES 2023, Spectricity, a startup based in Belgium, unveiled a new entrant to the competition: the S1 chip.

Spectricity claims the S1 is the first truly miniaturised and mass-manufacturable spectral image sensor for mobile devices — and the company is targetting sector dominance. Within two years, Spectricity boldly predicts the sensor will be inside every smartphone.

The bullishness derives from a singular focus: measuring “true colour” in smartphones. According to Spectricty, this is something that even the best smartphones still can’t do.

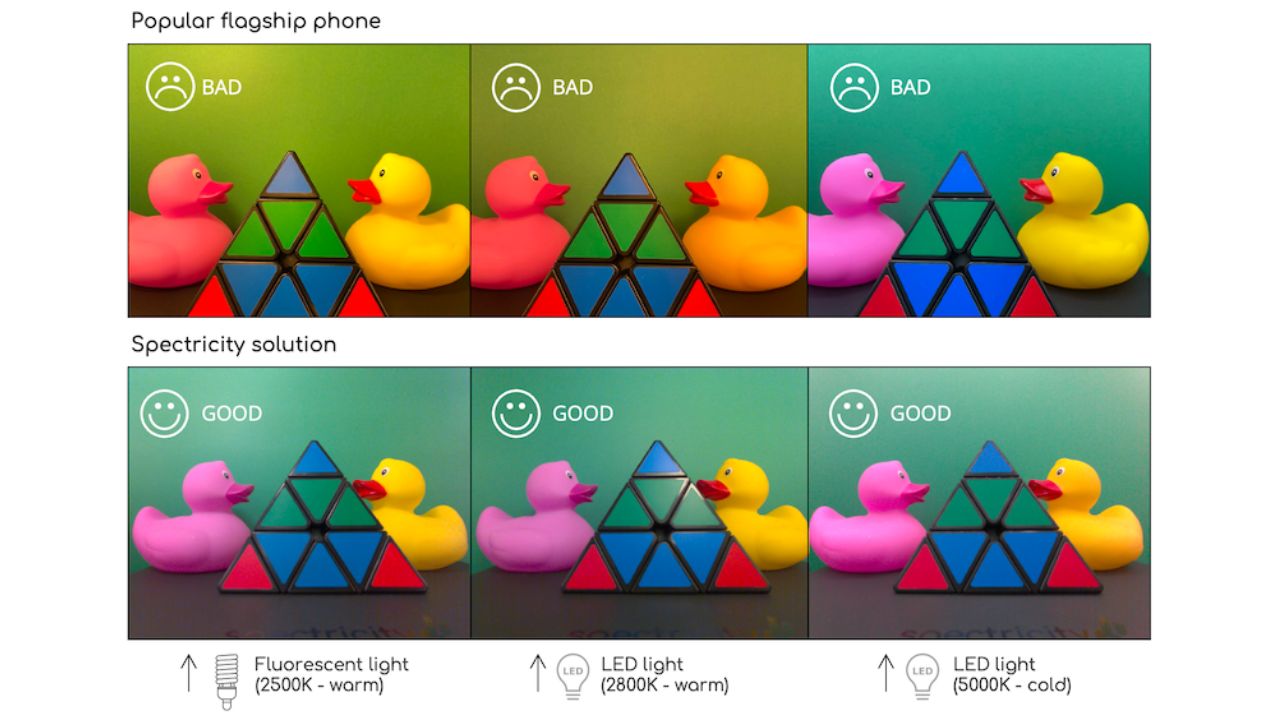

The problem stems from shortcomings in their white balance software, which is used to remove unrealistic colour tones. Our natural vision system does this remarkably well. When we see a white wall under sunlight or a fluorescent lamp, our brain adjusts the colour temperatures to make both scenes appear white. Smartphones attempt to do the same thing, but the results are often disappointing.

“None of these cameras can recognise true colour.

Limited by the three RGB colour channels of red, green, and blue, their auto-white balancing algorithms struggle to correct unnatural colour temperatures. As a result, photos taken under incandescent bulbs can appear more orange than under sunlight, while shady areas can look bluer.

“Even though there’s a lot of processing power behind these cameras, none can recognise true colour,” Spectricity CEO Vincent Mouret tells TNW.

To resolve this issue, the S1 sensor uses additional filters to analyse the spectral signature of an object. After sensing the light source in an image, the system corrects the colours accordingly.

Spectricity showed TNW the effects in a live demo. Under different lighting conditions, the pictures produced by the S1 were compared to photos taken by high-end smartphone cameras.

Although the results of demos aren’t always replicated in reality, the colours rendered by the S1 appeared far more consistent under diverse illuminations.

“With our solution, you can have the same colours whatever the lighting condition,” says Spectricity application engineer Michael Jacobs.

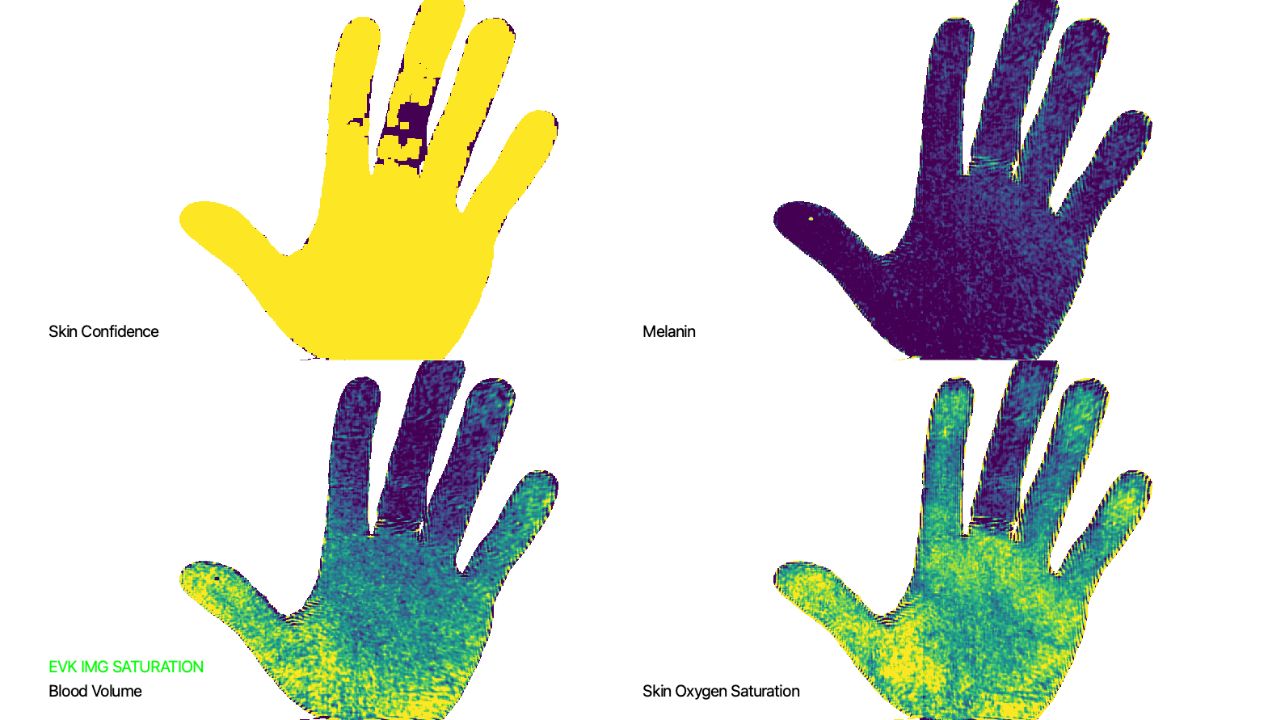

The ambitions for the sensor extend beyond better photos. As the S1 can capture the full visible and near-infrared range at video rates, the imager could enhance numerous mobile applications. Spectricity envisions using the sensor for remote cosmetics, e-commerce, ID verification, skin-health analysis, and even smart gardening.

A key component of these plans is the S1’s improved rendering of skin tones. Smartphone cameras are notoriously bad at capturing darker skin, which limits the inclusivity of photos. It also inhibits any apps that use skin analysis, from melanoma detection to virtual makeup.

The S1’s recognition of darker skin could broaden access to the benefits.

Smartphone giants are also ploughing fortunes into colour fidelity, but Specriticity says they still can’t compete with the S1 sensor. This confidence emanates from a long and narrow scientific focus.

Spectricity began life as a spin-out of the Interuniversity Microelectronics Centre (IMEC), a research lab for nanoelectronics and digital technologies. This connection has helped the startup amass 19 granted patents and 66 active applications, as well as 13 PhDs in their team.

To commercialise the innovations, Spectricity has set up a high-volume manufacturing line at the X-FAB foundry — which is now ready for mass production.

The S1 is currently under evaluation by major smartphone makers. Amid a global decline in mobile sales, Spectricity is betting that the sensor offers them an irresistible edge.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.