This week farmers found big chunks of metal from a SpaceX Crew-1 Trunk in a remote paddock in rural Australia. While it’s not an everyday occurrence, rocket body reentries (parts of space debris returning to Earth) are a trend that’s likely to increase.

Dr. Brad Tucker, Astrophysicist, and Cosmologist at Mt Stromlo Observatory at the Australian National University, went to check it out. He found that the pieces of rocket debris were 3 meters long and weighed 20-30kg each.

While it sounds like something cool to tell your grandkids, it points to a bigger problem – space junk.

What is space junk, and why is it a problem?

The term space junk refers to machines or debris left by humans in space and can be anything from dead satellites to paint flecks.

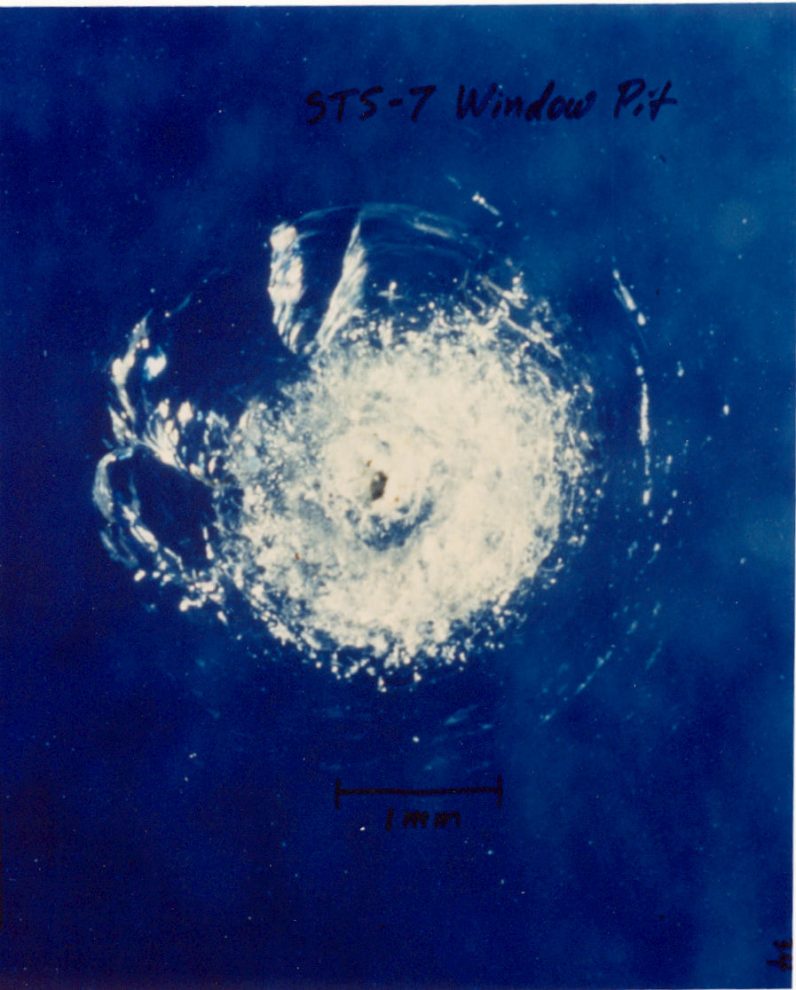

Most space junk orbits the Earth or gets burnt into the atmosphere. But it travels at extremely high speeds (approximately 15,700 mph in low Earth orbit), so even a tiny piece could hit spacecraft and cause damage.

According to NASA, there are approximately 23,000 pieces of debris larger than a softball orbiting the Earth. The Department of Defense’s global Space Surveillance Network (SSN) sensors track over 27,000 pieces of orbital debris.

And it’s not just a problem of legacy space tech debris from decades ago.

In 2020, over 60% of launches to low-Earth orbit resulted in abandoned rocket bodies in orbit. Worse, 24,000 satellites (and swimming robots) will launch in the next 10 years, opening the potential for even more space junk.

With space real estate increasingly crowded with junk, it may be difficult to position satellites precisely. It also creates a collision hazard for spacecraft and satellites. Just a speck of paint traveling at 17,000 miles per hour can cause catastrophic damage to a satellite.

Imagine a world without operational satellites. Weather tracking, live event broadcasts, stock market analytics, and ATMs would drive to a halt.

And, according to researchers, the space junk that survives the heat of atmospheric reentry in the form of debris is potentially lethal. In fact, it poses serious risks on land, at sea, and to airplanes.

The risk of being hit is increasing

Canadian academics recently published research in Nature Astronomy predicting a 10% chance of one or more casualties due to flying debris hitting a person (or infrastructure leading to injury) over a decade. The researchers note small rocket pieces crashing into an aircraft could cause hundreds of casualties.

For example, in 2016, SpaceX abandoned the second stage of a rocket in orbit. It reentered one month later over Indonesia, with two refrigerator-sized fuel tanks reaching the ground intact. Luckily it didn’t hit houses, animals, or people.

Where’s the space police when you need them?

Internationally, there is no clear and widely-agreed casualty risk threshold for falling space junk. NASA programs judge the acceptable risk of human casualty to odds of less than one in 10,000.

But what makes it worse is that your location increases your risk.

The Canadian researchers found that the latitudes of Jakarta, Dhaka, Mexico City, Bogotá, and Lagos are at least three times as likely as those of Washington, DC, New York, Beijing, and Moscow to have a rocket body reentry over them.

But has anyone been hit by space junk?

In 1997, Lottie Wiliams was hit by a flaming ball of space debris shooting through the sky in Oklahoma. Fortunately, she was unhurt.

But space junk has the potential to land on power lines, cars, trains, farm machinery, or in crowded spaces.

Meet space tech

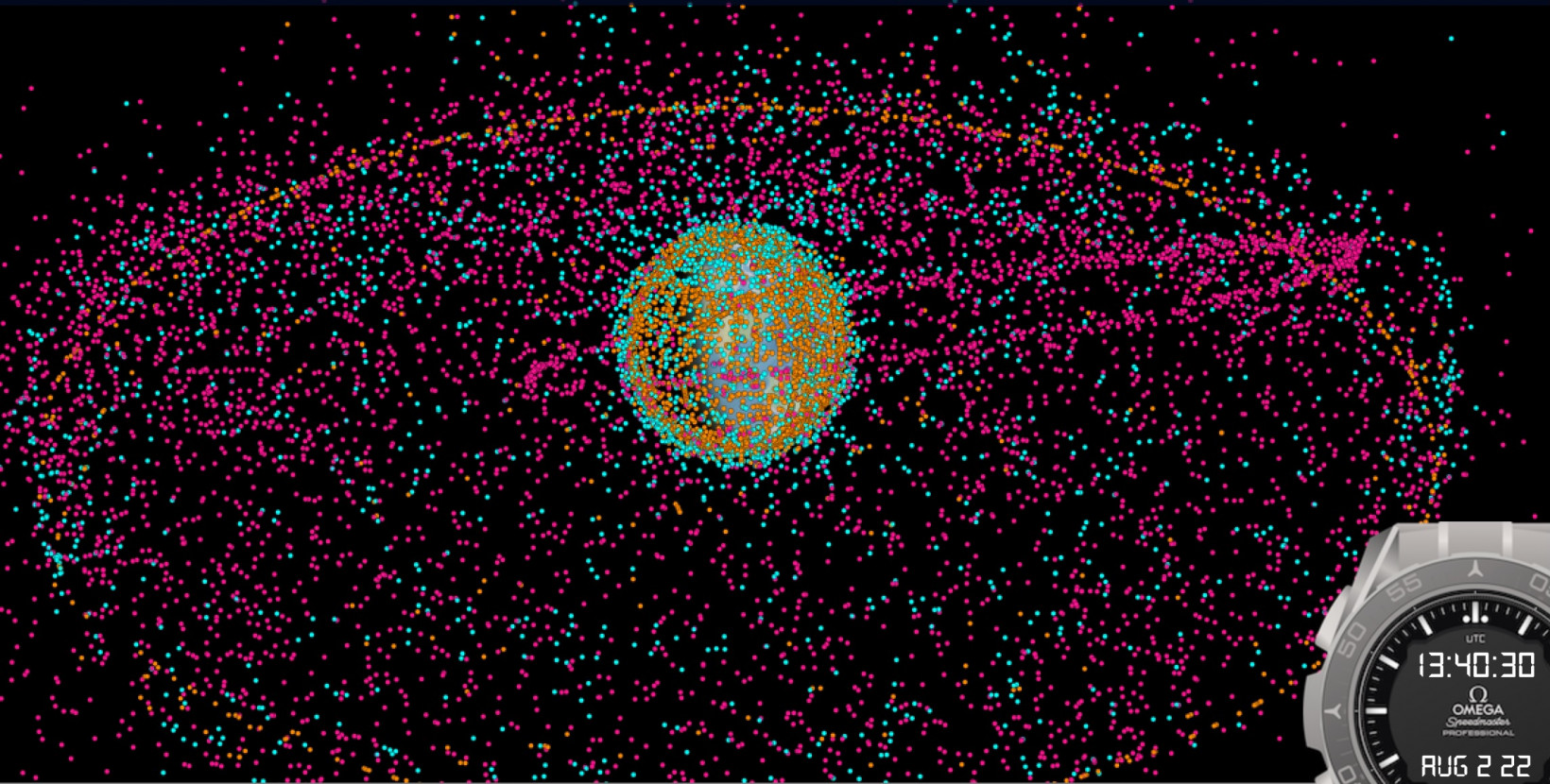

Tracking space junk has become an industry in itself. Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, is president of one company in the sector: the recently-launched Privateer.

Earlier this year, it released a space tracking app called “Wayfinder.” It visualizes and tracks orbiting satellites and space debris based on data from US Space Command, Planet Labs, JSC Vimpel (Russia), and SeeSat-L.

It’s helpful to space fans as well as researchers and lobbyists wanting to agitate for a response to the problem of space debris.

So how do we deal with this monumental problem? The Canadian researchers assert that the governments with populations most at risk from space junk should demand mandated controlled rocket reentries, with meaningful consequences for non-compliance.

Somehow I feel we’re a long way from this kind of action, but I suspect that soon, the problem will become too big for governments to ignore.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.