The end of summer also sounded the end of Germany’s €9 public transport ticket — a tenth of its usual price. Unsurprisingly popular with commuters, it left people wondering what was next.

This week the Berlin Senate has announced its plan to secure funds for reduced-price BVG tickets.

According to Mayor Franziska Giffey, a monthly ticket price of €29 for zones A-C has been agreed upon, with further discussion for outer regions and the rest of Germany.

But what was the impact of a €9 ticket on the environment, and did it result in fewer car trips?

Did the €9 ticket get people out of their cars?

Yes and no. According to the VDV, around 52 million tickets were sold nationally over the three months. A further ten million yearly subscribers automatically received discounted tickets.

A whopping one in five buyers had never used public transport before.

However, as I previously anticipated, the primary beneficiaries of the scheme were urban dwellers with access to public transport at regular intervals. The research found that ticket purchases were twice as common in urban areas.

Around 10% of 9-euro ticket users left their car at least once in favor of the bus or train. Excuse me if I find this a little underwhelming.

The research did find that new ticket buyers saved 15 kilometers per week in car travel while existing transport users saved 8km.

Still, research by the RWI-Leibniz Institute for Economic Research in Essen, also showed that car driving increased among 9-euro ticket buyers by an average of 18 kilometers per week in June compared to April — possibly as a result of improved summer weather.

So it’s an improvement, but I’d be more interested to see the figures at other times of the year when people are holidaying less, and inclement weather makes waiting for public transport less appealing.

What was the environmental impact of the €9 ticket?

The average saving in greenhouse gases (CO2 equivalents) is around 600,000 tons of CO2 per month: around 1.8 million tons of CO2 in the campaign period. This equates to over 387,845 gasoline-powered passenger vehicles driven for one year.

Analysis by traffic data company Tomtom for the German Press Agency shows that 23 out of 26 German cities had a reduction in traffic congestion, a leading cause of air pollution during rush hour — up to 14% in cities like Hamburg and Wiesbaden.

Additional social benefits

The €9 ticket increased regional and weekend travel, especially for people who usually can’t afford long-distance travel.

Plus, one of the biggest wins of the ticket was a significant reduction in fare evasion, a problem that has plagued the city for decades. In 2008, Udo Plessow, warden of Berlin’s Plötzensee correctional facility, told The Local that:

At least 155 of our 480 inmates have been jailed in lieu of payment for fare dodging… Actually, we have more than that, but when the men are sentenced because of another crime as well, they don’t get registered for fare dodging separately.

This number only increased. According to the Justice Senate Administration, in 2018, around 330 people were imprisoned annually for non-payment of fines for fare evasion. There’s something inherently problematic about incarceration for not-paying a transport fine.

The activists working towards free and low-cost transport

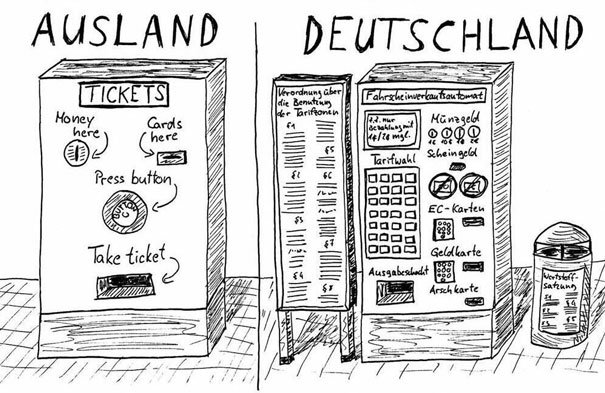

Like all cities, Berlin has its share of fare evaders. Its reasons vary from deliberate to accidental. We’re talking about a confusing transport system with a plethora of tickets which makes it easy for tourists to make errors and, consequently, vulnerable to fines.

The German capital also has a long history of resistance when it comes to paying for public transport. An example is a campaign where people with yearly tickets (who can bring someone with them for free after 8 pm and on weekends) wear a badge that invites ticketless people to stand with them when ticket inspectors get on a train.

A fund for fare dodging?

The day after the €9 ticket ended, a campaign popped up in Germany for cheap transport. Called 9 Euro Fonds, it invites people to pay a monthly €9 fee into a collective pot. Any fines are then paid by the collective.

It’s not the first initiative of this kind; similar schemes existed in France and Belgium in the late 1990s.

But the idea is perilous. First off, you have no recourse if the fund fails to grow large enough to cover fines. Further, violence from ticket inspectors during ticket control is not uncommon in Berlin, with BPoC and Asians overrepresented. What’s worse, a criminal record for fare evasion can serve as a black mark applications for permanent German or European citizenship.

Is the future free public transport?

There are over 100 public transport schemes globally. These range from temporary when pollution or smog is high to free buses in Kansas and a completely free in Luxembourg.

Ultimately, I’m unconvinced that Germany will ever introduce an entirely free public transport system — the operational costs are far too high And that’s before we look at the expense of improving regional public transport.

It’s far more likely we’ll see a carrot and stick ideology where it becomes less desirable to own, let alone drive and park a car, inevitably making public transport more appealing — alongside micromobility options.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.