It’s a question as old as the tech industry itself: can Europe compete with Silicon Valley?

This reared up again in my mind for two main reasons. The first is the recent(-ish) shift of Big Tech into being media entities. And the second? That’s Spotify’s struggles as a European stalwart in this field.

Let’s consider the first point.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen Silicon Valley shift its strategy and start investing heavily in media. You only need to look at Apple’s launch of the Apple TV+ and Apple Music streaming services, or Amazon’s foray into movies and TV series. I mean, the latter was behind The Rings Of Power, the most expensive television show ever made.

There are, of course, a myriad of reasons why Big Tech is investing in media, but one of the biggest is using it as a tool to hook people into their ecosystems.

“In the case of Amazon, due to its various revenue channels and methods of connecting with customers, it has a greater understanding of its users and their preferences through data,” Stephen Hateley says. He’s the head of product and partner marketing at DigitalRoute, a business that helps streaming companies understand their customer data.

He tells me that because Amazon “is not primarily or solely a media company, it can combine its customer accounts and upsell to them via its ecommerce, TV, film and music streaming, consumer electronics, and grocery delivery channels.”

For example, the company is able to spend money on shows and encourage people to subscribe to Amazon Prime Video. This comes bundled with Amazon Prime itself, meaning users have an incentive to use the platform to shop on.

Apple takes a similar approach.

In recent years, the company has realised that it’s close to hitting the ceiling of how many devices it can sell. From this point, growth will be tougher. Knowing this, it has shifted focus to services, effectively aiming to upsell software to its existing customers — and it’s working.

Apple not only gives customers free trials of its streaming services with new hardware purchases, but also bundles them together in its Apple One package. And again, like Amazon, it spends big on shows in order to attract people to enter its services ecosystem — with Ted Lasso being a prime example of this working successfully.

“This provides it with more opportunities to monetise its customers as well as collect a great amount of data on their preferences,” Hateley says.

Spotify’s struggles: An industry signpost

The thing is, all of the above isn’t particularly profitable — and especially not when it comes to the media side of things. In many ways, US tech companies are using streaming as a loss leader. They’re pumping billions into shows and movies with the aim of making money elsewhere, not through the media itself.

This is a huge problem to both media companies in general and European businesses in the same field. And guess who sits in both these categories? Yep, you guessed it: Spotify.

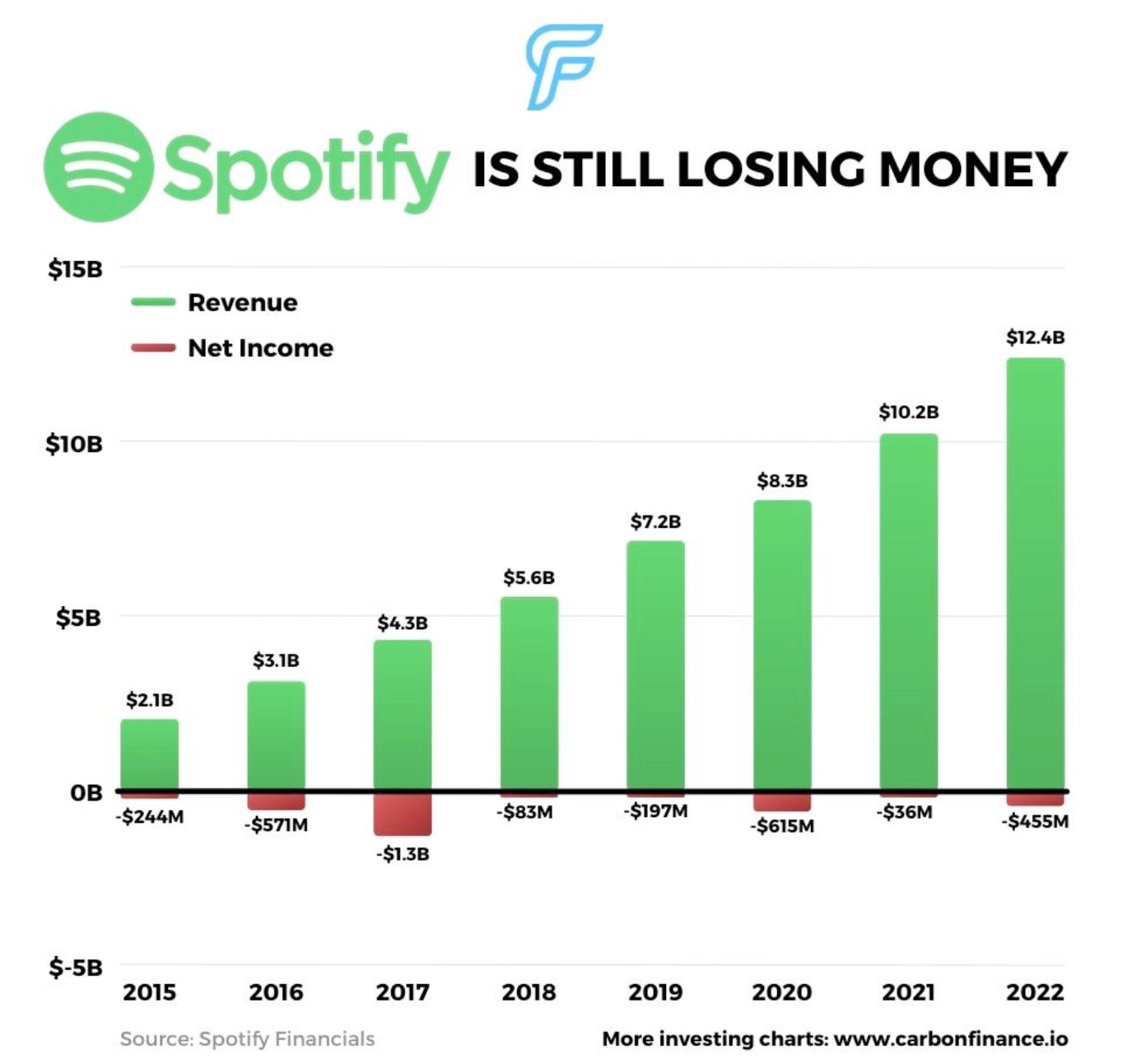

The Swedish company, which is broadly independent, is struggling to keep up with Big Tech. It pays its artists less than its biggest competitors, yet still hasn’t made a profit:

This shows in its behaviour. For example, it made a huge bet on podcasts, investing over a billion dollars in an attempt to bring a wider range of users onto its platform. While this had the clear benefit of making it a podcast leader, the company struggled to turn it into profit, leading to layoffs and a paring back of the approach.

This pattern is being played out across the entire European media landscape.

“US dominance can prove challenging for European companies attempting to claim their share of the market in any industry, and media is no different,” Hateley says, pointing towards how even organisations like the BBC are struggling in this environment.

This paints a picture of a sector being blasted away by Big Tech’s ability to spend and raises some important questions for the future of media.

Can European countries fight back? And do they need to?

“One way European media companies can compete with the big budgets of US firms is re-evaluating the type of content they’re putting out to audiences,” Marty Roberts tells me. He’s the SVP, Product Strategy & Marketing, at Brightcove, a streaming technology company.

Effectively, Roberts believes that US streaming giants create too many shows to market effectively. This is an opportunity for smaller entities to do “an amazing job at promoting a couple of new shows a month.”

Alongside this, he thinks that “[a] key strength for European media companies is hyper-localisation in niche markets.” He points towards either non-English language content, or getting particularly good at a specific genre, such as the success of Nordic detective dramas.

Jesse Shemen — the CEO of Papercup, a company that delivers AI dubbing for media companies — is similarly positive about prospects for European media.

“The current trend of bundling is opening up chances for unprecedented collaboration between European companies and US rivals,” he says. “We’re already seeing this in action, with Paramount Global’s partnerships with Sky and Canal+ just one recent example.”

This paints a rosier picture than I was expecting. The doom-and-gloom of European companies not competing doesn’t seem to trouble many experts, with them generally believing the businesses can thrive by not fighting US Big Tech, but instead working alongside it.

Yet is this unified, global approach a good thing?

One element that was brought up during my conversations was that the interconnected and worldwide focus of media now makes borders broadly irrelevant, meaning this focus on the success of European media specifically isn’t helpful.

“When it comes to investment capital, we live in a global village, where giant investors from the US, EU, UK, APAC, and anywhere can pour substantial capital into companies they believe in,” Maor Sadra says. He’s CEO and co-founder of INCRMNTAL, a data science platform.

This blurring of geographic lines, Sadra contends, is true of Spotify too. He points out that the company’s largest institutional investors include the UK’s Baillie Gifford, US-based Morgan Stanley, and Tencent Holidays, a Chinese company.

“The location of key management and employees in a connected world seems almost an irrelevant point of consideration in today’s age,” he tells me.

There’s no doubt that what Sadra and other experts say is true: we live in a global media environment and, for companies to survive, they need to accept that. Looking for outside investment or partnering with bigger organisations like Apple or Amazon is part-and-parcel of existing in this modern world.

This though doesn’t mean it’s not vital for Europe to maintain powerful media bodies.

You only need to look at how Hollywood and TV has benefitted America. It has expanded its cultural influence worldwide, becoming a form of soft power. Just consider, as one micro example, the global footprint of Halloween and Thanksgiving. For Europe to remain an attractive place, for it to carve out its own identity, it requires strong media.

Yes, it’s important to work together with these huge American organisations, yet European businesses in the same sector have to make their own mark too — and one way of achieving that is with tech.

Staying ahead of the wave

There was one theme that came up across many of my conversations on this topic of using tech to remain relevant: artificial intelligence.

“Localisation is one area where technology’s influence, especially generative AI, is being felt,” Shemen from Papercup tells me.

This is being trialled in a number of places already, with Spotify planning on cloning podcast hosts’ voices and then translating them into different languages. This trend will be hugely important for European media creators, especially if they’re making content in non-English. It almost goes without saying how much this could benefit smaller creators and media companies that fall into this category, as their potential reach can skyrocket.

Artificial intelligence will also be a vital part of the puzzle for European businesses when it comes to analysing data. If they can get access to forms of insights currently only available to gargantuan tech companies, they can alter their content to appeal and reach the masses, levelling the playing field.

The European route to success

If European media is going to survive Big Tech’s thrust into the space one thing’s for certain: it can’t stay stationary. Instead, the European industry needs to take advantage of its positive attributes and use them as best it can.

This should involve embracing its ability to create niche content, clever content partnerships, and investing in technologies that can help European content hit a wider audience.

Ultimately, the future of media streaming in Europe is one of balance. While there’s a lucrative future available by partnering with bigger organisations, it can’t risk losing itself in the process. Currently, there’s no real way European media bodies can compete with the bottomless wallets of Silicon Valley. What they can do though is ensure they stay relevant.

The secret to achieving this isn’t all that secret — being nimble and open minded.

Don’t act so shocked: age-old questions often have age-old answers, after all.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.