With carmakers committed to sustainability targets for incoming decades, they are finding second life use cases for discarded cars and their components.

Recently, Hyundai has found a new way to give a second life to preproduction prototypes. Rather than conventionally crushing them or using them for accident testing, it’s released a video showcasing a “rebirth” of various Ioniq 5 car components to create an air purifier. Hyundai originally built the test car for noise, vibration, and harshness tests.

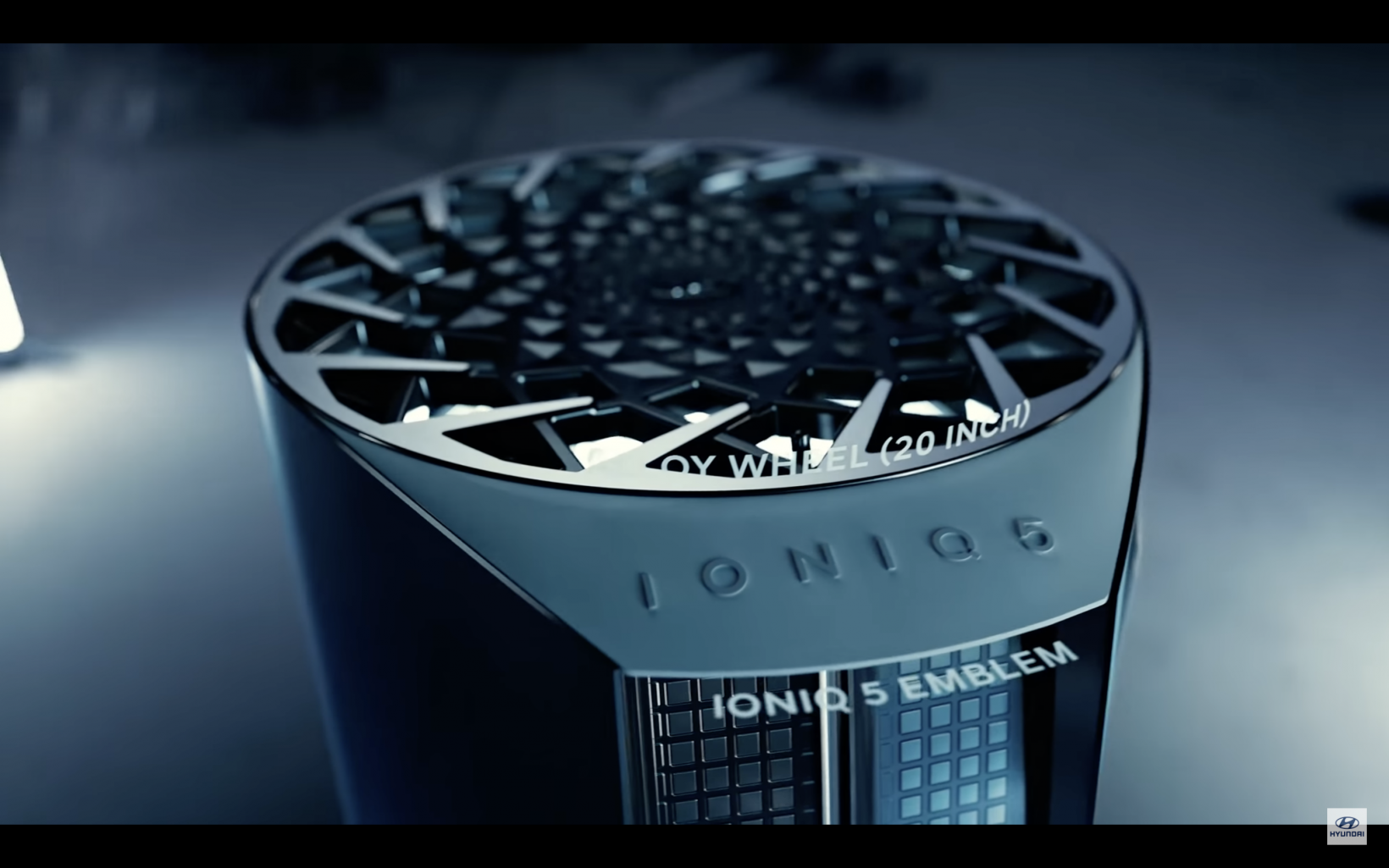

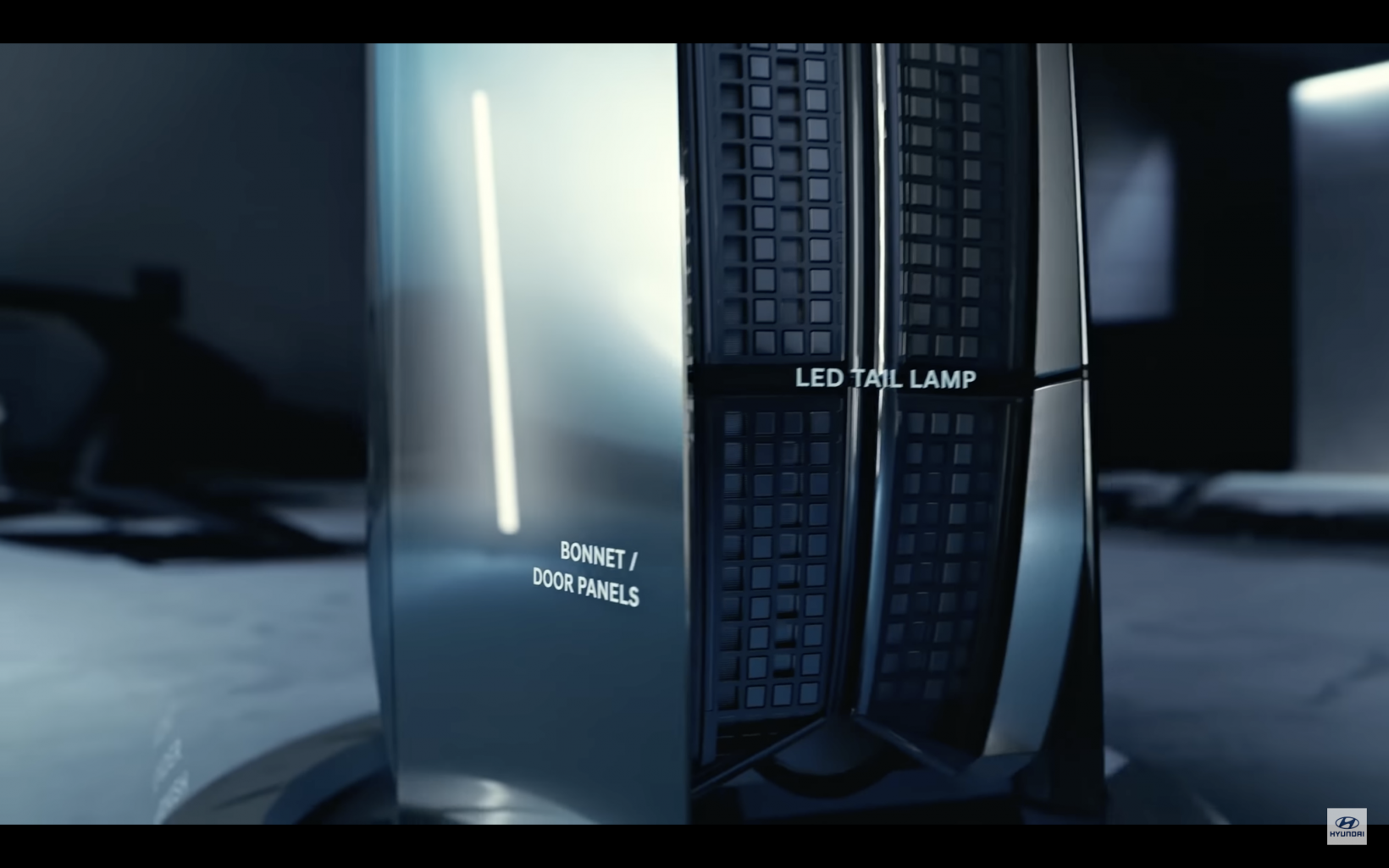

The air purifier’s functionality comes from the original car cabin air filter and cooling fan. A 50 cm alloy wheel tops the air purifier case, with its side panels made from bits of the car’s doors and hood.

The casing is decorated with the Ioniq 5’s emblem pixelated LED taillamps and the digital instrument cluster readout.

This particular upcycling is admittedly more about marketing than creating functional retail or mass-market products. But it’s part of a more significant trend of circular design, which considers the lifespan of product design beyond its original purpose. This is particularly big when it comes to repurposing EV batteries.

Second life batteries are big business

Lithium-ion batteries generally last about 10 -15 years in powering an electric vehicle. However, they have a residual capacity of more than 80 percent beyond their vehicle functionality.

As a result, they are being increasingly used for stationary electricity storage systems, where they are cheaper than new cells and can live for a further 10 years.

Further, the carbon emissions generated when the batteries were produced are spread sustainably across two service lives — one in the car and one in the storage system.

´

In Germany, a joint energy transition project between RWE and Audi is using 60 decommissioned lithium-ion batteries to provide temporary storage for about 4.5-megawatt-hours of electricity at the site of the RWE pumped-storage power plant in Herdecke, North Rhine-Westphalia.

In Japan, rail operators are replacing batteries in emergency power supplies at railroad crossings with used batteries from Nissan Leafs.

Even better, unlike lead-acid batteries, these repurposed lithium-ion batteries come with a control system attached, making it possible to check the battery’s status remotely. This facilitates predictive maintenance, informing rail staff of the battery’s status before its voltage becomes too low.

A second life limited by poor uniformity

McKinsey and Co predict that the second life battery supply for stationary applications could exceed 200 gigawatt-hours per year by 2030. However, they highlight several barriers to this, including:

- Refurbishing complexity due to lack of standardization and fragmentation of volume.

- The absence of standards regarding guarantees regarding second life battery quality or performance.

- A lack of standard performance specifications for second-life applications.

An opportunity for new business models

McKinsey also suggests that the trend of car buyers owning EV batteries may shift due to their residual value in second life applications. This may result in a model of EV battery leasing which enables the auto or battery maker to maintain ownership of the battery’s second revenue stream.

It’s a model we’ve already seen in Ather and Bounce scooters in India. In Germany, Swobbee has created an alternative business model, facilitating battery sharing for escooters and ebikes. It will be interesting to see what kinds of solutions evolve for EV auto batteries.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.