You may have noticed an influx of ads for furniture on your Instagram feed after looking for a new chair for your work-from-home setup, or promoted posts for a coffee shop that you’ve only ever walked past. Your phone’s apps collect and share a lot of information—from your location, to your browsing habits, to your search history.

But for iPhone owners, that’s about to change in significant ways.

Apple announced in June 2020 that this spring it would begin requiring iPhone, iPad, and tvOS apps to get consent to share people’s data with third parties like data brokers and other apps.

The move is a complete rethinking of privacy rights. Data collection has long operated under the premise that millions of people are fine with being tracked, their movements and behaviors shared and sold, unless they explicitly say no. Privacy settings are usually opt-out and often buried deep in an app’s settings. But soon people using iPhones will be asked to explicitly opt in to having their data shared among advertisers, apps, and data brokers.

Apple CEO Tim Cook explained the change in a Jan. 28 speech at the Computers, Privacy , and Data Protection conference.

“Technology does not need vast troves of personal data, stitched together across dozens of websites and apps, in order to succeed. Advertising existed and thrived for decades without it,” Cook said. “If a business is built on misleading users, on data exploitation, on choices that are no choices at all, then it does not deserve our praise. It deserves reform.”

Some tech companies—namely the ones that rely on amassing personal data to sell advertisements to companies looking to reach specific demographics—are less than happy.

In Facebook’s 2020 fourth quarter and full-year earnings report, the company predicted a major hit to its ad targeting capabilities because of Apple’s privacy changes. And Google has warned app publishers that they “may see a significant impact” to their ad revenue after the policies take effect.

Facebook declined to comment for this story. Google declined to comment on Cook’s remarks.

Privacy rights advocates, meanwhile, are pretty pleased.

“This is actually a very good thing for most people,” Pete Snyder, senior privacy researcher at Brave Software and the co-chair of the W3C Privacy Interest Group, said. “The state of people’s privacy on iOS devices will be dramatically better than it is today.”

While the forthcoming changes are significant, they don’t completely shield you from being tracked, particularly by the biggest tech firms, like Apple itself. Here’s a rundown of what to expect.

What will change under Apple’s new rules?

Currently, apps gather all sorts of information about you as you use them—that’s not going to change. What will change is how that information is shared with third parties, like data brokers and other tech companies.

Right now, the vast majority of apps you download, whether to an Apple or an Android device, track you in pretty much the same way, through a unique identifier.

The Identifier for Advertisers, or IDFA, is a standard device identifier Apple created in 2012. Google has its own version for Android devices called the Google Advertising ID, or GAID.

So if you’re looking at pictures of cats on one app, and then checking basketball scores on another, both apps would get your IDFA to share with advertisers and data brokers who link your online movements to build a more complete profile of you.

And there are other ways the data you generate by using an app gets shared. Apps can gather and share granular details of your actions through “in-app events” collections, like what you’ve clicked on and what you’ve looked at.

Under the current opt-out model, you can clear your history by resetting your IDFA or limit tracking by setting your IDFA to all zeroes. You can do this under Advertising in your privacy settings on your iOS device. Research from AppsFlyer, a mobile advertising firm, found that only about 25 percent of people turned this setting on in 2020.

But that will become an opt-in model when Apple’s privacy change kicks in.

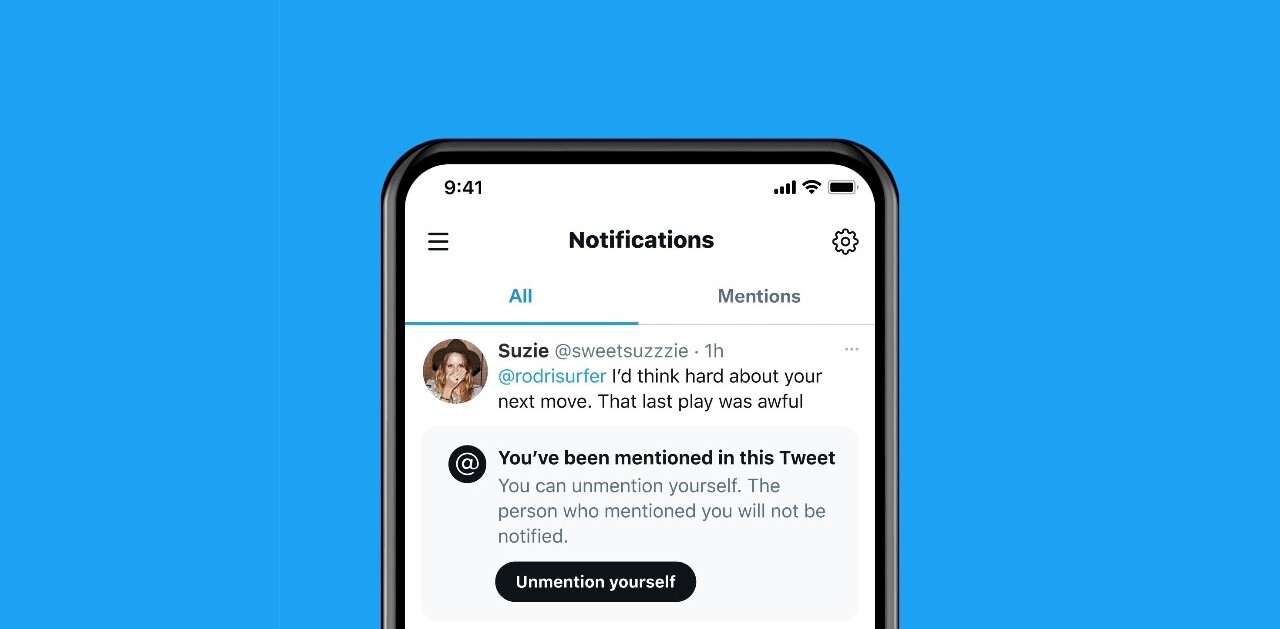

Apple says its update will take effect in early spring, with iOS 14.5. Once that happens, any app that collects data about you and shares it with other companies for cross-tracking and advertising purposes will be required to get permission first.

Without that consent, apps won’t be allowed to share any data they collect about you with other companies or data brokers for advertising purposes. Companies can still share data for other purposes—like preventing fraud or for analytics.

The changes only apply to Apple devices—Android’s app store has announced no similar changes.

And even for iPhone users, apps can still gather information about you under the new rules; they just can’t share that information for advertising purposes.

Apple’s new policies prohibit tricks for getting consent, too. An app won’t be able to prevent access to its features because you won’t let them track you or offer incentives to users who allow tracking. The prompt can only show once—so you can’t be spammed with requests, either.

Apps that don’t show the prompt aren’t allowed to share your data with third parties and won’t get your IDFA.

The change could be huge.

AppsFlyer found that after several developers implemented Apple’s tracking request prompt early, 99 percent of people decided against giving them permission. Some apps will likely decide to simply stop sharing tracking information instead of implementing the prompt.

Serge Egelman, research director of the Usable Security & Privacy Group at the International Computer Science Institute, says most people don’t want to be tracked.

“The reason why more people don’t opt out is because it’s very complicated,” Egelman said. “Given that we know that most consumers don’t want to be tracked and aren’t making informed decisions, it makes sense that you would switch to an opt-in model.”

So how can I still be tracked after the changes?

Companies can still track you through their own services, but they can’t share that information with anyone else without your permission. So although Spotify, for instance, can’t share data about your searches on its app to Facebook without your consent, Facebook can still use data you generate on its own services, including Instagram and Oculus, to build an image of who you are and what you like and use that profile to sell ads.

The more powerful the innate data-tracking capabilities of the app, the better they’re likely to fare under these changes, says Johnny Ryan, a senior fellow at the Open Markets Institute focused on privacy and antitrust.

A company like “Google can come along and say, ‘We’re going to put the entire market in ourselves. Instead of having thousands of companies who provide advertising space, everyone should come to us,’ Ryan said.

In fact, Google has already said it won’t bother with data-sharing on Apple devices anymore.

“We will no longer use information that falls under [App Tracking Transparency] for the handful of our iOS apps that currently use them for advertising purposes,” Matt Bryant, a Google Ads spokesperson, said.

Google will have a plethora of data it collects on a first-party basis to use for advertising and will still be able to collect third-party data from apps where people have opted in, Ryan said.

How will Apple enforce its policy?

Here’s where things start to get tricky, according to experts.

Apple controls the IDFA tool, so the company should have the means to ensure apps are not using it without consent. But experts say it will be hard for Apple to prevent apps from sharing data in other ways and worry the company is going to rely too heavily on the honor system.

“The app developer can say they don’t do any tracking and then at the same time collect a bunch of different data points to uniquely identify that user over time,” Egelman said. “There’s not really any way that Apple or anyone else can automatically identify that unless they’re individually analyzing this particular app and what it’s sending.”

While Apple has capabilities to identify third-party trackers embedded in code during its app review process, following up to make sure that the first-party data isn’t being shared without permission can be difficult.

“If we learn that a developer is tracking users who ask not to be tracked, we will require that they update their practices to respect your choice, or their app may be rejected from the App Store,” Apple said in a white paper on privacy released in January.

Apple declined to comment on how it will enforce its new policies.

Sean O’Brien, principal researcher at ExpressVPN’s Digital Security Lab, said it’ll be important for Apple to establish a rigorous auditing process to enforce their new policies.

“You need a combination of both automated scans and manual review, and you have to try to have a slower review process before you accept apps into your store,” O’Brien said.

This article was originally published on The Markup and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.